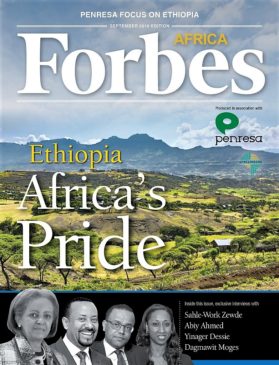

Addis Ababa Showcasing Ethiopia’s Great Economic Leap

Middle-class aspirations blossom among the new high-rises, though poverty is far from conquered

Middle-class aspirations blossom among the new high-rises, though poverty is far from conquered

The capital of Ethiopia seems to be one vast building site. As the high-rise blocks, broad avenues and roundabout take shape, a new Addis Ababa is springing up. The priority for the regime is to build at all costs.

Ethiopia (population 85 million) is the second largest country in Africa and busily modernizing. It is ruled by the People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, which is set on turning the country into the tiger of Africa.

Once synonymous with acute poverty and famine, Ethiopia has over the past decade enjoyed one of the highest growth rates in Africa – between 8% and 10%. Although a third of the population still live in poverty – on less than $0.60 a day – an urban middle class is appearing. Its members cannot compete with western countries, as earnings and careers are still very uneven. But they share a fierce determination to improve their lot.

Mekonnen Tilahun, 32, is an accountant. He is ambitious, switching jobs every two years. In eight years his wages have increased fivefold. To save money, he still lives with his mother. Were it not for inflation Tilahun would count himself very lucky. One day, if he puts enough money aside, he may marry. With “no more than two children”, he promises. Meanwhile, he works hard. His only luxury is the sports centre where he goes three nights a week. His younger sister wants to emigrate to the US, but not him. “Everything remains to be done here,” he says.

Hanna, one of his workmates, came home last year for the same reason after finishing university in France. “I realized that in Europe I would never matter as much as I do here,” she says simply. She thinks the country is “starting to open up to the outside world”.

Lily and Mimi Kassahoun hesitated a long time before deciding to head home. The two sisters finally returned to Addis Ababa at the end of 2011. It was a wrench because after 20 years in Canada it felt like home. “Our parents kept saying: ‘Why won’t you come back to Ethiopia? Business is booming here’,” they explain.

Lily and Mimi Kassahoun hesitated a long time before deciding to head home. The two sisters finally returned to Addis Ababa at the end of 2011. It was a wrench because after 20 years in Canada it felt like home. “Our parents kept saying: ‘Why won’t you come back to Ethiopia? Business is booming here’,” they explain.

Three months ago Lily opened a restaurant in the Bole neighborhood, appropriately named “Oh Canada”. The place is already packed. “I paid attention to three things generally lacking in Ethiopia: clean toilets, quality service and atmosphere!” she says brightly. The bureaucracy, unreliable contractors, the need to train staff, the irregular supply of ingredients and the constantly rising prices bother her, though. “I thought it would take six months to open. It took three times that much. You have to learn to be patient here, but I’ve no regrets,” she adds.

Sales of beer are another unusual indication of Ethiopian gentrification. Bernard Coulais heads the local branch of BGI Castel, which sells wine and beer all over Africa. “I aim to bring beer to everywhere in Ethiopia,” he brags.

In Angola, which is heavily urbanized, average per capita consumption now stands at 50 litres a year. In predominantly rural Ethiopia it is only four. “But things are changing so fast. Our sales are progressing at the same pace as the road network and electrification. It’s a revolution. We can barely keep up with demand,” he adds.

Ethiopia has achieved almost 100% school enrolment, largely thanks to former Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, who ousted the dictatorship in 1991 and ruled the country with until his death in August 2012.

Come back in five years’ time, It will be a modern city, with broad tarmacked avenues and ultramodern blocks and shopping malls.