Celebrating a living legend: Miruts Yifter

By Zecharias Zelalem

Talkative, playful and observant, the elderly statesman sitting upright in the hospital bed appears oblivious to the panic stricken sentiments of some of his visitors who arrived at the Bridgepoint Hospital in Toronto, fearing the worst. After all, it was only a couple of weeks earlier that Ethiopian state media had reported that the man, who is also one of the country’s greatest ever Olympians, had succumbed to illness and died. An outpouring of grief would follow over the course of the next couple of days, until the man himself, Miruts Yifter, spoke to a journalist saying he had yet to depart this world. The athletics icon has been hospitalized for months suffering from a collapsed lung which is made more complicated due to his advanced age. His condition currently prevents him from leaving the premises, ruling out any trips back to Ethiopia for the foreseeable future.

Draped in his hospital gown, Miruts enjoys the company he has. There are five or six chairs placed around his hospital bed. One visitor leaves only for three of four others to enter and spend up to half an hour with him, chatting and ensuring the man international media dubbed “the shifter” is in good spirits. He is rarely alone. He has a flip phone near him which he says he keeps to speak to people inquiring about the best visiting times, but also to receive calls from his admirers, Ethiopian and non Ethiopian around the world checking up on him. I encountered Miruts some three years earlier at an Ethiopian event in Toronto and for those who have seen Miruts prior to his hospitalization, he is noticeably frailer and looks slightly strained. Hooked up to tubes which facilitate his breathing, it produced a lump in my throat when I recall this man being one of the best long distance runners on the planet in his heyday. But the fierce looking wolfish glare in his eyes is still there today, and Ethiopians who have grown up watching reruns of his Olympic achievements will still be able to recognize Miruts after a careful second or two of observation. The man now sipping from a thermos of Atmit, an Ethiopian creamy formula of milk, wheat and various flours is the same man who immortalized his name in Olympic history thirty six years earlier in Moscow.

Bib 191 bode his time, trotting at a pacemaker’s speed, waiting for the perfect instance to pounce and deliver what after over nine kilometers he calculated would be the killer blow to all the gold medal aspirations of those he was trailing and leading. Grimacing, the wireframed bright orange kit clad presence didn’t appear too menacing among the pack of four or five running stalwarts. He appeared to simply be going with the flow. It was anyone’s guess who among the quintet would be able to deliver the coup de grace that would render one superior to the rest.

But Miruts Yifter, aka “the shifter,” was no drifter. In peak physical fitness and fueled by a determination to finally claim his long deserved coronation that cold war politics denied him four years earlier in Montreal, Miruts would firmly grab his destiny by the horns. With something like two hundred meters to go, he put it into another gear, one more gear higher than anyone else on that Sunday night in Moscow had. His move was decisive, his lead unassailable, with over eighty thousand people looking on and cheering in astonishment at the packed Moscow Olympic Stadium, Miruts Yifter ran across the finish line and into the history books which will testify of his feats for eternity and a day. Some thirty six or so years later, British sports announcer David Coleman’s commentary for Miruts’ last lap dash can still make the hairs on the back of the neck of any athletics enthusiast stand.

“There goes Yifter the shifter! That’s why they call him “the shifter!” Viren’s (Lasse) challenge has evaporated. The Olympic gold medalist looks certain to be, Yifter the shifter from Ethiopia! He really is flying, the power is there, and he has done what we expected, DESTROY them on the last lap!”

Miruts Yifter’s unforgettable 10,000 meter gold medal winning performance at the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, would be followed by another gold medal a mere four days later in the 5,000 meter race. At the 1980 Olympics, Ethiopia racked up four medals, two gold and two bronze, and registered what was at the time their best ever Olympic showing. Miruts became the first ever Ethiopian athlete to win two gold medals at the same Olympics, a feat not equalled for another twenty eight years, when both Kenenisa Bekele and Tirunesh Dibaba won the double at Beijing 2008.

At the facility in Canada, far from Moscow, the city of his coronation, far from the town of his upbringing Adigrat, or the city he was paraded through as a national hero Addis Ababa, his reported demise created a near chaotic atmosphere. The hospital wasn’t prepared for what would come. It appears that the nursing staff at the hospital didn’t realize they had an internationally renowned sportsman at their venue.

“The day the news came out that he had died, the hospital received phone calls non-stop! We couldn’t deal with all the calls and later started directing all calls to the hospital straight to his ward,” one of the nurses tells me. “It was amazing. I didn’t realize just how famous he was.”

“Mr. Yifter had hundreds of visitors in two days,” said the front desk secretary. “Some were crying others were in clear shock. I had one grieving woman tearfully ask me if the body was still here. She wouldn’t believe me right away when I told her he was alive!”

The Bridgepoint Hospital staff is now informed of the stature of the man in room 4.183. One of the nurses taking care of him let me know that he is of Nigerian descent. “After I learned of his greatness, I came to appreciate and admire him as much as you do. What he has done was great for Africans as a whole!”

It isn’t clear how the news of Miruts Yifter’s death came about. But the EthiopikaLink radio program in Ethiopia came to the conclusion that false rumours spread on the web were first generated by an Israel based Ethiopian diaspora entertainment and gossip news site. From there, it gained momentum and somehow made its way to the Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (EBC) news desk. On Wednesday November 9th 2016, EBC’s nightly sports show started off on a solemn note. Reporter Mulugeta Kifle announced to millions of viewers in Ethiopia and around the world that Miruts Yifter had died.

Two days after the broadcast, EBC released a retraction note, apologizing for misinforming viewers. In the fallout soon afterwards, EBC sports news chief editor Neway Yimer took full responsibility and apologized on a local radio talk show. He deactivated his Facebook account the same day and told the radio show that he had also submitted a letter of resignation to EBC. “I cannot shift the blame,” said Neway ruefully. “I take full responsibility and would like to apologize to Miruts, his family and admirers.” In a twist of events, Binyam Miruts, son of the man at the center of it all, called the radio show and forgave Neway on air for the mishap saying it was human to make mistakes.

As social media users and reporters sheepishly started deleting the obituaries to Miruts hastily written in the immediate aftermath of Miruts’ “death,” the living legend himself says the episode demonstrated just how much of an impact his exploits have left on generations of Ethiopians.

“I don’t have money and I would rather be back home in Ethiopia. But my people have showered me in love. I’m not forgotten among my people.” Miruts brought two or three in the room close to tears when he said this.

This statement testifies to an all too sad reality about Ethiopia’s sporting icons of the seventies and eighties. During the communist regime of former Ethiopian President Mengistu Hailemariam ( who ruled from 1974-1991), the prize money and presents bestowed unto national heroes pale in comparison to the millions up on millions of dollars made in endorsement deals, prize money, lucrative business ventures and investments that Ethiopia’s world class athletes of today can earn. Despite his status as a beloved athlete and hero, he wasn’t looked upon to keenly by the elite of the newly installed EPRDF government of Meles Zenawi which took power in 1991. They saw him as too friendly to the previous communist regime and he was no longer in the limelight of celebrity stardom. In 2002 he immigrated to Canada and lived in the Ottawa area and coached athletics at universities as well as Ethiopian running clubs based in the area.

This statement testifies to an all too sad reality about Ethiopia’s sporting icons of the seventies and eighties. During the communist regime of former Ethiopian President Mengistu Hailemariam ( who ruled from 1974-1991), the prize money and presents bestowed unto national heroes pale in comparison to the millions up on millions of dollars made in endorsement deals, prize money, lucrative business ventures and investments that Ethiopia’s world class athletes of today can earn. Despite his status as a beloved athlete and hero, he wasn’t looked upon to keenly by the elite of the newly installed EPRDF government of Meles Zenawi which took power in 1991. They saw him as too friendly to the previous communist regime and he was no longer in the limelight of celebrity stardom. In 2002 he immigrated to Canada and lived in the Ottawa area and coached athletics at universities as well as Ethiopian running clubs based in the area.

Depictions of Miruts a political beneficiary or a regime supporter are far from accurate. He has always been no more than a world class athlete with a burning sense of patriotism. At his first Olympic showing in 1972 (Munich), he managed to win a bronze medal in the men’s 10,000 meter race, his first Olympic medal. It also happens to be the first ever bronze medal won by an Ethiopian athlete. But for the 5,000 meter competition, Miruts is written down as having missed his race (DNS abbreviated for did not start). An article on his official Olympic page profile states that the reason he didn’t show up for his heat is shrouded in mystery. But Miruts has explained why he didn’t appear at the starting docks.

“My coaches took me to the mixed zone to warm-up and left me there. But then, they arrived late and by the time they took me to the race marshals, the race had already begun.”

For Miruts, the confusion amongst his coaches that caused him to miss out on a huge opportunity was heartbreaking. But upon his return home, he would have salt rubbed into his wounds. The government of the time accused Miruts of purposely missing the race and had him imprisoned for treason. Only weeks after winning Olympic bronze, he would find himself behind bars, declared a traitor to his country. “They said that I had deliberately failed to compete and threw me into jail,” a tearful Yifter later told the IAAF.

Despite his being jailed, Miruts wouldn’t let his passion for running dampen even in the slightest. He simply adjusted. Instead of practicing with the Ethiopian national team at the country’s top facilities, he would now train as a member of a prison athletics team. He did so with the hope that the maintaining of his peak form and raw talent would convince officials to lobby for his release in time for the 1973 All Africa Games. He was successful and after serving three months in prison, Miruts would later board a plane for Lagos, Nigeria. There he romped to victory in the 10,000 meter event, coming in nearly a minute before silver medalist Paul Mose of Kenya would finish. He would collect the silver medal in the 5,000 meter event, the event catalyst to his then recent misfortunes.

After rebounding from his brief spell in jail to become African champion and a favourite for the upcoming Montreal 1976 Games, Miruts Yifter would suffer another setback that would nearly foil his Olympic aspirations. At the time, the openly racist apartheid regime in South Africa was prohibited from competing in sporting competitions, banned by every African sport governing body across the continent. This was due to the country’s only white selection policy of athletes that denied Black South Africans the chance to represent their country. But the immoral nature of that country’s sporting policies didn’t prevent the All Blacks, the New Zealand rugby national side from visiting South Africa to take them on in friendly competition. New Zealand’s sending a team to apartheid South Africa was widely condemned among Africans who would call for the International Olympic Committee to ban New Zealand from the Olympics which were then only months away. The IOC refused to penalize New Zealand, which was taken as tacit approval of apartheid practices. Twenty five African countries protested the IOC’s dillydallying by boycotting the Montreal Games. Among them, Ethiopia. Due to these matters beyond his control, Miruts Yifter would not compete at Montreal 76 and missed out a chance to win Olympic gold and make amends for the confusion which saw him miss his 5000 meter heat four years prior.

Miruts, disappointed, remained a diplomat. “We did it for South Africa, who was fighting against Apartheid. That at least, lessened the pain (of missing out on Olympic competition).”

A long distance runner’s age of peak fitness tends to be in his mid twenties. The problem with Miruts Yifter is that accurate documentation of his age is somewhat hard to come by, his IAAF profile lists him as having been born in 1944, but elsewhere 1938 has also been indicated as his year of birth. By the time of his missing out on the 1976 Montreal Olympics, according to these dates he could have been aged anywhere between thirty two and thirty eight. The fact that he was a world beater and an Olympic favourite deep into his thirties speaks of his dedication to his craft, his commitment to what must have been a grueling training regime, and his love for sport.

Nevertheless, he refused to give up on his Olympic dream. He remained committed to his goal of becoming Olympic champion, despite the fact that he could be as old as forty-two by the time the 1980 Moscow Olympics would be in swing. Miruts dodged the topic of his age whenever confronted by journalists. At one such encounter, Miruts refused to tell reporters his age giving an answer that is the stuff of legends:

“Men may steal my chickens, men may steal my sheep. But no man can steal my age!”

While some may have guessed that his best days were past him, Miruts quickly proved any doubters wrong. A year after the Montreal Olympics, the first ever IAAF Continental Cup was held in Dusseldorf Germany. In Germany representing the African continent for the first time, Miruts won the 10,000 gold AND finally tamed his demons, taking the elusive 5,000 meter race gold as well.

But a much more symbolic achievement was ahead of him. Denied a chance to compete in Montreal, Miruts was selected as part of the African side for the subsequent 1979 IAAF Continental Cup, which was also scheduled to be held in the city of Montreal.

In Montreal, Miruts Yifter reigned supreme, winning the double, taking gold in the 10,000 meter and 5,000 meter races once again, and some say earning a crowning moment that should have taken place at the same venue three years earlier. There were no lingering doubts that his advanced age would slow him down as the Olympic year loomed large.

“I told journalists who saw me to count my enthusiasm, not my age! I told them you need Ethiopian motivation to win races.”

That Ethiopian motivation appears to have served him well.

After his dominance in back to back IAAF Continental Cup competitions, Miruts, despite being in some cases ten or twenty years older than most of the competition in his field, was once again considered an Olympic favourite. The eternally long four year wait had ended, Yifter the shifter had arrived for Moscow 1980.

July 27th 1980 saw Miruts’ defining moment as an athlete. The afore-described scintillating finish to the men’s 10,000 meter event at Moscow Olympic Stadium saw the senior talisman flanked by a couple of his younger budding countrymen in Mohammed Kedir and Tolossa Kotu, challenge the Finnish dominance of the event. Defending Olympic champion Lasse Viren and his compatriot, Kaarlo Maaninka made it a faceoff between Ethiopia and Finland. In the end, the young stallions were no match for the old horse. Miruts “shifted” past everyone with hundreds of meters to go, finally winning that long awaited gold medal, some eight years after his first bronze medal, eight years after being sent to prison for missing a race, eight years after other athletes would have thrown in the towel after the indignity subjected to.

Maaninka would come in next for second place, while Ethiopia’s Mohammed Kedir would win the bronze. Tolossa Kotu finished fourth. This would be the first time in Ethiopian Olympic history that more than a single Ethiopian athlete would be on the same podium. The feat would next be repeated twenty years later at Sydney 2000, when at the same 10,000 meter event Haile Gebreselassie and Assefa Mezgebu would come in first and second respectively, but Miruts Yifter and Mohammed Kedir will forever hold the distinctive honour of being the first Ethiopian athletes to “own the podium” at the Olympics.

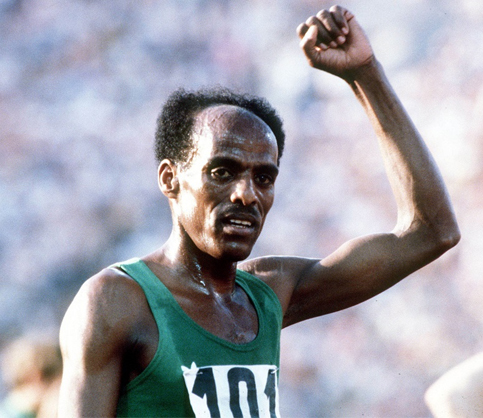

Five days later, Miruts would win the 5000 meter event and the double, confirming his status as the best in the world. There would be no missing out this time. Just as he did in the 10,000 meters, with less than a lap to go he sprinted away from his nearest challengers and rode off into the sunset. As he did almost a week earlier, he celebrated his win with his signature left arm raised into a clenched fist, before being embraced by his teammate and partner in crime, Mohammed Kedir. Perhaps the most widely known image of Miruts is the one taken immediately after the race, with his arm raised triumphantly.

Miruts Yifter’s gold medals were celebrated in Ethiopia. He became a national icon and his success served to lift many others. Most notably, two time Olympic champion Haile Gebreselassie credits Miruts as having inspired him to follow in his footsteps and take up long distance running.

At his hospital bed in Toronto a couple of weeks ago now, Miruts asked me about the city of Montreal. About three or four days before my trip, I had called him to let him know I had planned on making the trip from Montreal. Miruts’ ever the warm host, told me that he’d love to meet me but that he wouldn’t be able to leave the hospital to greet me. I was stunned. He felt obligated to go out of his way and meet me somewhere in town. I had to assure him that I wouldn’t get lost and that I’d find my way to him!

Montreal was his city of ups and downs. His eyes flickered with nostalgia as he recounted his glory days in the French speaking Canadian city. He went over his duel with American Craig Virgin at the big O (the name given to Montreal’s Olympic Stadium). I had to later look up the video on YouTube to see what he was talking about. In that race, the duo ran almost side by side for the entirety of the race until Miruts ran away with it and won by a nearly fifty meter gap.

I wasn’t born during Miruts Yifter’s accolade littered athletics career. But younger Ethiopians grew up seeing the reruns of his Moscow triumphs on television sport shows that the image is well engraved into the psyche of Ethiopians of all ages. This was evident in 2004 when Miruts Yifter returned to Ethiopia and paid the Olympic team a visit. The athletes, most of whom weren’t around to see him race, greeted him as a father figure some with tears in their eyes.

People are filing in and out of his hospital room. As one group of visitors leave, another promptly walks in, warmly embraces Miruts and sits down. Miruts an ever alert participant in conversation, switches seamlessly from the Amharic language to his native Tigrigna, depending on the people addressing him. Many members of Toronto’s Ethiopian community know him personally and hearing their discussions with him was entertaining in itself. One man came to tell Miruts about the illness of a mutual friend.

Man: “Tadele is sick, he might need to be operated on.

Miruts: “Tadele?”

Man: “Yes.”

Miruts: “Impossible! I saw him a week ago, he looks fine to me.”

Man: “But I heard that he is suffering.”

Miruts: “Forget what you heard! Didn’t you also hear that I had died? But I’m still here with you! People say a lot of things!”

The whole room bursts into laughter.

Miruts’ condition is slowly but surely improving. When I had visited him, he had resumed eating for three days and needed less rest than before. He was feeling stronger he told me, in no little part thanks to the moral boosting visits of admirers and acquaintances.

“People from as far as Washington DC, New York and California have come to see me,” he says in a jovial tone. “Athletes running for clubs and universities have visited me and told me I was there hero. Being loved is something irreplaceable that money cannot buy and I can only thank the Creator for this,” Miruts is clutching an Orthodox Christian cross as he says this.

“People from all over the world have called me. Haile, Kenenisa, all the athletes have comforted me and encouraged me on the phone. I appreciate the kindness of my people.”

I ask him about his former teammates.

“Yes they call me, especially Tolossa Kotu and Mohammed Kedir. When Mohammed called me the other week, he was hysterical, crying on the phone because he had heard that I had died. I had to calm him down.”

I learn that Mohammed Kedir is currently based in Switzerland. The old teammates have a bond of brotherhood that will remain with them for the rest of their lives.

Humble, sweet and an entertainer, Miruts is clearly a people person. The aftermath of the announcement of his death has seen a great influx of people calling and visiting him. Miruts has clearly thrived in this atmosphere, as his health once reported as declining, has improved in recent weeks.

Miruts Yifter the man, the legend, should be celebrated while he is alive. So often have Ethiopian national heroes seen their legacies feted only after they have left this earth.

In 2010, Ethiopia’s greatest ever footballer Mengistu Worku passed away at age 70. He was known for his scoring three goals in the 1962 African Cup of Nations tournament as Ethiopia won a major international trophy for their first and only time to date. He spent the entirety of his career at Ethiopian club Saint George. Only just after his death did Saint George decide to retire jersey number eight in his respect. It is a mystery why the club decided never to bestow such an honour to him while he was alive. Mengistu Worku didn’t get to have the chance to see his legacy celebrated by a nation despite his mammoth achievements in Ethiopian football.

Miruts Yifter is very much alive. He is a living legend and has so much to share in treasured experience and inspiring stories. He is an athletics icon and the mark he left on global sports will have people reminiscing about him for generations to come. While that semi raised left arm and fist will leave an eternal imprint on the mythological Mount Olympus, it should be a joy to partake in the latter chapters of the life of a man who has attained mythical status in the sport. Indeed to be number one in athletics well into one’s thirties and forties is unheard of. One can simply refer to what had become of Haile Gebreselassie and Kenenisa Bekele’s careers after they hit thirty.

“Miruts” which loosely translates to “ripened” or “quality,” is indeed as his name indicates, of a fine breed of men who were destined to write history. The King of Moscow was born in Adigrat; his emblem, the Ethiopian flag. A proud patriotic people will forever bask in the glory of his accomplishments.

Some perspective here. Miruts is certainly a great runner. Let us not forget Ethiopian runners of the past hardly received the plaudits they deserved. Nothing exceptional in the case of Miruts. Miruts’s failure to go in the proper gate at Munich could be simply explained as his [and other Ethiopian athletes] unfamiliarity with the instructional language and with modern venues; remember this is in the 1970s and 1980s. Guess who his coaches would blame for such failure. Along with Miruts should be the forgotten bunch starting with Belayneh Denasmo who could have easily eclipsed Mirtus.

Haile GS’s tribute in NYT today sounded superficial. Haile said, “For me, he is the best-ever athlete Ethiopia ever had after the great Abebe Bikila.” Really? Think again Haile. Take off your false humility and exploitative veneer. Does Mamo Wolde register? Mamo was jailed by the present government on charges that he had participated in the 1970s Red Terror and later released though Mamo continued to declare his innocence. In the end, no one can take from Miruts his achievements and the pride he gave us all. May he rest in peace. My sympathies to the family.