Who is coming to Ethiopia?

by Tony Hickey

Last year in 2016, according to the latest figures issued by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, tourist arrivals to Ethiopia reached the figure of 868,780.

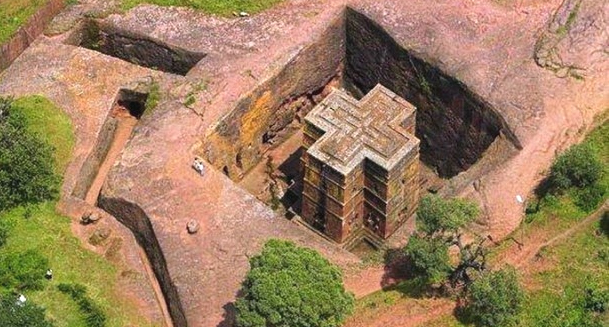

Let’s take another figure – in 2009 EC, the number of foreign tourists who visited Lalibela, arguably Ethiopia’s premier tourist site, amounted to 25,069, or just under three percent of the total number of tourist arrivals. So where did the missing 843,711 go? Not to the Simien Mountains National Park which in the same period only received 10,685 foreign visitors.

The answer to this apparent conundrum lies in the World Tourism Organization (WTO) definition of “tourist”, or to quote the 19th century American novelist, Mark Twain: “Figures often beguile me,” he wrote, “particularly when I have the arranging of them myself; in which case the remark attributed to Disraeli would often apply with justice and force: ‘There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.’

The fact is the vast majority of the 868,780 visitors in 2016 probably never left Bole International Airport or its environs. Under the WTO definition, “Tourism comprises the activities of persons traveling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes.”

And as another commentator mentions, “In terms of duration, only a maximal duration is mentioned, not a minimal. Tourism displacement can be with or without an overnight stay.”

There is absolutely no doubt, Ethiopia has wonderful tourist attractions, and this has been well attested to by a score of tourist guide books, such as Lonely Planet and the Bradt Guide, documentary films, countless newspaper and magazine articles, and postings on the internet. But the steady increase in tourist arrivals, as per the statistics in recent years, owes more to the activity of Ethiopian Airlines than to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MoCT), the Ethiopian Tourism Organization (ETO) or the hard working Ethiopian tour operators.

Ethiopian Airlines has made Addis Ababa a global hub, with daily flights to six destinations in China, and to nearly the same number to India. It has linked Africa to North and South America, to Europe, and to the near and far East. Some 2,000 Chinese visitors transit through Addis Ababa every day. Going the other way is a very large number of Nigerian and West African travelers, off for business in China and other countries in the southeast.

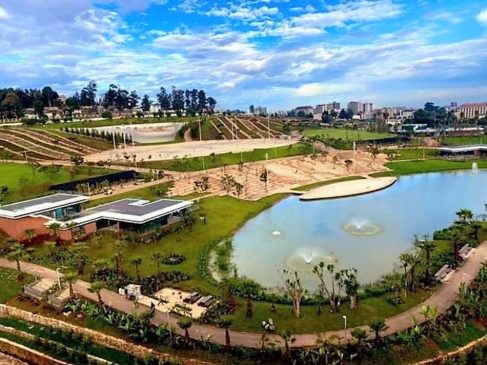

The fact that Ethiopian Airlines links Africa to the world is great, but we should not base our tourism development plans on figures for arrivals in and transit through Bole International Airport, nor extrapolate from those figures that Ethiopia will be in the top five tourism destinations in Africa by 2020, or that we will get 2.5 million tourists in the same year. (An estimated 1.5 million foreign tourists visited the Cape Town Victoria and Alfred Waterfront in Cape Town in 2016 – Lalibela has a long way to catch up).

As Singapore has shown, there is a lot that can be done with transit passengers in terms of getting them to spend more money for the few hours they are around, but the MoCT and the ETO need to talk more about how we can boost vacation tourism numbers. The last statistical breakdown in tourist arrival numbers was done by MoCT in 2012, when the numbers of vacation tourists was given as 191,417, or 32.1 percent of the total of 596,341.

Most people in the industry felt that this number was inflated, as it neither correlates with hotel occupancy rates, nor with entrance fees paid at historic sites and national parks. People coming in to the country for business, conferences, diaspora visiting family or in transit, tend to put down “tourism” as “reason for visit”, a) because it is simpler, and b) because other visas are more expensive and more difficult to obtain.

The real figure was almost certainly somewhere below 100,000. (In a recent interview in London, Yohannes Tilahun, CEO of ETO, said of the 868,780 visitors last year, some 86 percent or 747,150 were business visitors to Addis Ababa).

Last year, in 2016 and from the end of 2015, following anti-government protests and demonstrations in parts of the Oromia and Amhara regions, and in some areas of those regions, the loss of life and destruction of property, the governments of tourist sending countries issued travel advisories which told their citizens to “avoid all non-essential travel to (specified areas) in Ethiopia’s Amhara and Oromia regions”.

The result was devastating for Ethiopia’s vacation tourism sector, as opposed to the transit, business and conference tourism sector, as company after company cancelled trips they had booked, and often paid for.

The result was devastating for Ethiopia’s vacation tourism sector, as opposed to the transit, business and conference tourism sector, as company after company cancelled trips they had booked, and often paid for.

Hotels in Bahir Dar, Gondar and Lalibela were empty, as were cultural restaurants, azmari bets, bars and souvenir shops. The same was true down the Rift Valley, through Zwai, to Bale, Negele Borana and Yabello. Areas off the list, like Awash, Harer and the Omo Valley also took a hit, as tourists going by road had to pass through the so called “danger zones” to get there. (Tigray was not included in the “danger zones”, so tourism there received a boost, with tourists flying in to Mekele.)

Everybody in the very extensive tourism value chain, in addition to hoteliers and shop owners, down to fuel station owners, guides, kiosk owners and shoe shiners, felt the pinch.

The figures quoted above for entrance fees to Lalibela and the Simien Mountains were down by 50 percent when compared to the previous year.

But overall tourist arrivals, as defined by the WTO, did not seem to be very much affected. After all, if you are a Chinese businessperson on your way to Cape Town, or a Nigerian businessperson on your way to Guangzhou, travel advisories from Western governments about “avoiding all non-essential travel to Ethiopia’s Amhara and Oromo regions” is not going to make you abort your trip. Why should they, you’re only going to be in Addis Ababa for a few hours.

But for western tour companies, ignoring your government’s travel advice means invalidating your clients’ travel insurance. If any of your clients get into an accident, like falling in the hotel bathroom in Bahir Dar, food poisoning from a restaurant in Goba, or something totally unrelated to the political situation, they are not covered, and your company is liable. That is why even after the situation had calmed down, until the travel advisories were lifted, foreign tour companies stayed away.

This year as the new tourism season gets underway, there are signs of recovery, but numbers in vacation tourism are still not where they were two years ago. The tourists flow cannot be simply turned on again like electricity. People cancel their trip, and book somewhere else. And the recovery is necessarily fragile – any signs of breakdown in law and order, and once again the negative travel advisories will be released and tourists will be warned from traveling to Ethiopia.

Coming back to statistics and figures again, Ethiopia’s tourism sector, both public and private players, needs to focus on two sets.

The first is job creation, and income generation. What job opportunities will the expansion of vacation tourism, and I am thinking here of tourism outside the capital, bring to high school, college and university graduates? More though and planning has to be given here after all, surely the whole point of developing a tourism industry is not simply to entertain foreigners, but to bring benefits to the population of the country. (What measures could be taken here should be the subject of another article).

The second set of figures is about carrying capacity. Neither Ethiopia’s historic and cultural sites, nor its national parks, can cope with an influx of millions of visitors. It would simply not be sustainable. Carrying capacities for all Ethiopia’s tourist sites need to be assessed and the necessary actions taken.

There has been a tendency to leave tourism development to market forces. I believe we need a more political approach – we need to frame an ideological critique of tourism development as it has taken place in Ethiopia and other countries around the world, and ensure that what happens in the best interests of the Ethiopian people, socially, economically and environmentally.

Author: Tony Hickey is the general manager of Ethiopian Quadrants PLC. He can be reached at ethiopianquadrants@gmail.com.

The article first appeared in the Addis Ababa-based English newspaper The Reporter