Expunging Ethiopian football’s Eritrean legacy

By Zecharias Zelalem

“I’m Negash Teklit!” said the man looking towards the Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (EBC)’s camera, with a radiant smile, beaming with pride. Beyond the greying hair, it certainly didn’t look like the years had taken a toll on him. Tall, still firmly built, correct posture Negash Teklit’s physical exterieur is a far cry from that of many former sporting stars who’ve reached middle age. Typically, a decline in fitness of former footballers is most visible a decade or so after they no longer adhere to the rigorous training regimes that they’ve built their careers on. Putting on pounds and a potbelly, footballers are often a shell of their formerly lean, fit selves. But decades after retiring from a storied career, Negash not only looks quite fit, he almost looks young enough to be able to resume his career, perhaps for a season or two.

On this day some five months or so ago, Negash was clad in a suit and red tie combo that complimented his cheery demeanor. He was among a slew of Eritrean sporting stars present at Asmara International Airport to welcome the visiting Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. A historical occasion, the Ethiopian leader’s arrival in Eritrea and meeting with Eritrea’s President Isaias Afewerki sealed an end to decades worth of political hostility that followed the devastating 1998-2000 Ethio-Eritrean war. A festive occasion for the peoples of both countries, the creme de la creme of Eritrean society, athletes, entertainers and various celebrities were present to mark the monumental restoration of diplomatic ties. Ethiopians and Eritreans celebrated an end to the political gridlock and international media extensively covered what was a truly refreshing, feel good story.

Among those in Asmara who greeted the visiting Ethiopian delegation, Zersenay Tadese. Eritrea’s first ever Olympic medalist and a world class long distance runner in his heyday. He was accompanied by a number of the country’s top athletes and cyclists, all dressed in national team attire. Perhaps unmatched in sentimental value however, was the presence of the group of ageing footballing icons, all smartly dressed in suits and ties, led by the charismatic Negash Teklit.

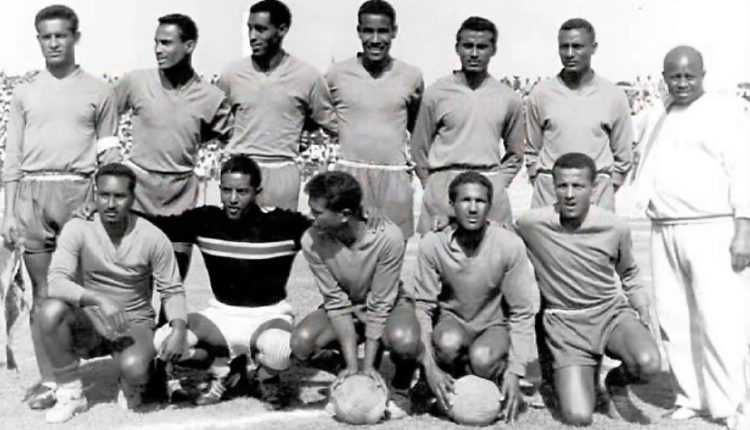

That’s because many of them made their names as members of the Ethiopian national team. They burst onto the scene in the sixties and seventies, prior to Eritrea gaining its independence from Ethiopia in 1991. The likes of Tekle Kidane and Italo Vassallo are part and parcel of one of the most cherished achievements in Ethiopian sporting history, the 1962 African Cup of Nations victory. Eritreans formed the backbone of the Ethiopian national team squad during its finest hour, some fifty six years ago now. During that tournament, Ethiopia defeated Egypt 4-2 in a hotly contested final where eight of Ethiopia’s starting eleven were Eritreans. 25,000 fans crammed into the Addis Ababa Stadium (then known as the Haile Selassie Stadium) and watched team captain Luciano Vassallo receive the glittering trophy from Emperor Haile Selassie. Some of the stars on the day have since passed away. But others, now in their seventies and eighties, are living proof in the flesh of Ethiopia’s stint as champions of Africa, unfathomable to even imagine nowadays.

“Here’s Italo Vassallo!” Negash introduced the retired star to the EBC camera crew, as if he needed an introduction. Italo, 78, scored the winning goal of that final against Egypt in extra time. Born to an Italian soldier and an Eritrean mother during the Italian military occupation of Ethiopia, he is the half brother of older sibling, Luciano Vassallo, 83. The EBC journalist recognized the former striker and greeted him, congratulating him on the attaining of peace between the two countries. Clearly flattered, Italo grinned perhaps astonished that a reporter from Ethiopia of this day and age could recognize him a half century after he and his friends left their mark on the game.

Despite their contributions to the country’s sporting development, the class of 62 would soon face isolation and rejection. In 1974, a popular uprising brought about the ousting of Emperor Haile Selassie and an end to the country’s imperial monarchy. The elderly king would be detained and eventually murdered in custody. The new Derg government leadership, composed of army officers and self declared communist revolutionaries, didn’t take a liking to the stars of the national team. They deemed them to be imperialists, beneficiaries of the old guard and bourgeoisie of the ousted king. No longer allowed to thrive in the limelight for their heroic achievements, players disappeared into obscurity, some after having their properties and wealth nationalized by the communist regime. In 1978, team captain Luciano Vassallo was nearly killed at the behest of a Derg government official. He subsequently fled to exile in Italy. On the wrong side of the political upheaval, others were reduced to abject poverty.

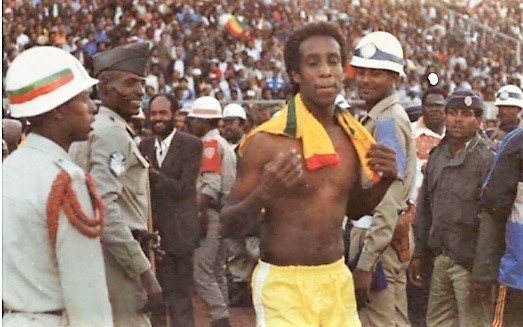

By 1987, Ethiopia’s footballing prowess had dipped considerably and the country was no longer a regular contender for the continent’s top prize as it once had been. In fact, sealing qualification was no longer guaranteed. The stars of 1962, who could have been deployed as trainers, scouts and coaches for the up and coming generation of footballers, were mostly excluded from any such involvement. Ethiopian football fans, the pessimistic bunch they can sometimes be, were quick to accept that a reversal of the country’s footballing fortunes was no longer on the horizon. But with Ethiopia set to host the 1987 regional CECAFA Cup tournament, the sporting establishment were eager for that taste of triumph that had evaded them for 25 years. Ethiopia did eventually triumph, defeating Zimbabwe on penalties in the final after 120 minutes ended in a draw at Addis Ababa Stadium. A young fearless trailblazer of a man, 21 year old Negash Teklit stepped up to take the first of the spot kicks. Cold blooded and unmoved by the pressure bestowed upon his young shoulders, the referee forcing him to adjust the position of the ball placed on the spot didn’t phase him. He calmly stepped up and smashed the ball into the top corner, far out of the reach of the Zimbabwean ‘keeper. The victory sparked wild celebrations and is still fondly remembered in Ethiopian folklore to this day. None of Ethiopia’s subsequent CECAFA Cup triumphs (2001, 2004 and 2005) trigger as much emotion in sporting fans today as the memory of the 1987 win. The reverberating joy was so much that, the country’s communist dictator Mengistu Hailemariam ordered the lifting of a late night curfew across Addis Ababa. Security forces had been granted the authority to immediately execute youths in the streets of Addis Ababa if they were found outside late at night on the suspicion that they were clandestine opposition elements. Countless youths were massacred for merely defiling the curfew, including people who were just making their way home from work. On the night that Negash Teklit and his teammates secured the regional football crown, they also secured for the residents of Addis Ababa, a night of gaiety and sheer happiness, free of extrajudicial slaughter.

Negash Teklit shirtless during the 1987 CECAFA Cup (Image: EBS)

Negash Teklit would go on to coach the Eritrean national team and until recently coached the Eritrean U-20 side. Negash Teklit’s personal contributions to the Ethiopian game remain largely unknown to younger football fans today. The breakout of war between the two states in 1998 saw Eritrea and Eritreans depicted in Ethiopian media as the enemy. Hostile rhetoric from Ethiopia’s political leadership increased, including from Prime Minister Meles Zenawi who openly stated that, “if the government says we don’t like the colour of their eyes, then they (Eritreans) should get out.” Hundreds of thousands of Eritreans, of all walks of society were subsequently deported from the country. The devastating war caused tens of thousands of deaths on both sides before ending in a protracted stalemate. Among those promptly ordered to leave the country and deported with little more than the clothes on his back, Italo Vassallo. Scorer of the most important goal in Ethiopian football history.

“I love Ethiopia, I gave everything I had for the Ethiopian people,” Italo said in an interview with an American based Ethiopian website a few years after being deported from Ethiopia. He slammed the Ethiopian government and its officials. “I knew about national pride and honouring the flag before most of them were even born,” a clearly irate Italo said at the time.

The ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) government did all it could to expunge the achievements of Eritreans from the records. This meant that although the 1987 CECAFA Cup would be brought up from time to time, Negash Teklit’s name and likeness for instance were to never be seen or heard in Ethiopian state media.

The EPRDF regime that overthrew the communist government in 1991 had a policy that frowned upon reminiscing about historical events that could possibly portray past governments in a positive light. As has often been the case in Ethiopia, the new leadership exhibited a keen desire to wipe its predecessors from the records. Sporting heroes, who often set out with no other desire but to reach for the stars, were ostracized by governments who deemed them propaganda elements of bygone eras. It wasn’t only Eritreans. The likes of long distance runner Miruts Yifter, double Olympic gold champion and at his peak during the communist era, were deemed Derg regime apologists by the new EPRDF regime. Miruts spent over a decade in exile in Canada before passing away in 2015. The country’s greatest ever footballer and the national team’s top scorer during that 1962 coup, Mengistu Worku, was himself more or less hidden from public view by state media controls, until news of his dying from cancer in 2010 emerged.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s ascension to power has noticeably mellowed the unrepentant and oppressive EPRDF. The past 27 years of the party’s rule has been characterized by a razor thin tolerance for dissent and the mass arrests, torture and killing of political opponents and outspoken citizens. But beyond keeping the population inline and in submission to the idea of indefinite rule by an elitist clique of powerbrokers hailing from the northern region of Tigray, the EPRDF also aggressively peddled its revisionist version of Ethiopian history. The history books, media and entertainment, closely monitored and controlled by the regime, were used to systematically erase all mention of historical events and individuals who were even remotely linked to any entity deemed hostile to the EPRDF narrative. Unfortunately for the likes of Gilamichael Teklemariam, starting goalkeeper of the 1962 AFCON winning squad, this meant that his identity as an Eritrean would rob him and his exploits of the recognition they deserve. His identity would render him a casualty of Ethiopia’s political fallout with Eritrea. As the vast majority of the squad members of the class of 62 were Eritreans, this has resulted in the Ethiopian football federation shying away from even organizing events commemorating the greatest day in the country’s footballing history.

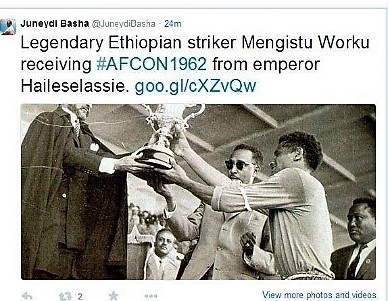

Fourteen African national sides have won the continental crown. Most honour their AFCON victories by sewing in commemorative stars atop the crest on the national team jersey to remind fans and pundits alike of the shirt’s glorious past. From the fourteen, Ethiopia is one of three AFCON winning countries to have never added a commemorative star to its national team kit. The Ethiopian Football Federation (EFF) has never gone on record to explain why, although it’s an open secret that paying homage to the stars of yesterday in such a fashion wouldn’t be permissible in the formerly autocratic EPRDF’s Ethiopia. Although Ethiopia’s status as a one time African champion remains constantly cited by journalists today, the men who delivered the prize have been almost scrubbed from collective memory. In fact, a few years ago, when former EFF President Juneidi Basha tweeted a picture showing the captain of the squad, Luciano Vassallo receiving the trophy from Emperor Haile Selassie, he was unable to identify Luciano and mistakenly captioned the post “Mengistu Worku receiving #AFCON1962 from emperor.” When the President of the football federation is unable to identify one of the greatest footballers produced by the country, one can safely assume that the effort to delete them from the psyche has been somewhat successful.

Luciano Vassallo has lived much of the past four decades in Rome. In any other African country, the captain of the sole major tournament winning squad would be showered with accolades, named a hero of the nation and have sports venues named in his honour. Luciano Vassallo is relatively anonymous today when compared to some his counterparts in Egypt, Ghana and Sudan. In 2000, he published his biography but due to the book being written in the Italian language, it never penetrated the Ethiopian market and isn’t likely to have generated many sales. By 2007, a Google search of Luciano Vassallo yielded no immediate results. In recent years, he has been interviewed by foreign based Ethiopian news outlets. Often critical of the government and understandably so, he has come across as bitter with some of his public statements. In the aftermath of the Ethiopian national team’s elimination at the group stage from the 2013 African Cup of Nations, Luciano posted a comment via his Facebook page in which he derided the players, calling them “losers.” Last year, he granted an interview to Italian journalist Damiano Benzoni in which he made several previously unheard of claims about former EFF and Confederation of African Football (CAF) President Yidnekachew Tessema. According to Luciano, Yidnekachew, who coached the 1962 AFCON winning squad, actually despised Eritreans and tried to limit their presence in the national team. Yidnekachew served as CAF President for 15 years until his death in 1987 at age 65 after a long battle with cancer.

It would be pretty difficult to establish the veracity of those claims which date back to half a century ago. It would be much easier to say that these are the utterings of an increasingly resentful elderly man. However, there is truth to the claims that a lifetime of servitude to the Ethiopian sporting cause hasn’t garnered him the honour and respect someone of his caliber deserves. Luciano was a friend of the former Milan great and Italian international Cesare Maldini, who passed away in 2016. But while Cesare would go on to remain a mainstay in Italian football, accepting media gigs and top level coaching jobs decades after retiring from the game, Luciano, whose achievements in African football certainly do mirror those of his friend, did not. Like his half brother Italo, Tekle Kidane and others, his Eritrean roots and prominence in Imperial Ethiopia would not sit well with the country’s successive governments. Ethiopia’s political inflexibility had effectively excommunicated them from enjoying retirement amongst the people he bedazzled and entertained on the football pitch for over a decade.

Luciano is Ethiopia’s second highest goalscorer at AFCON tournaments with 7 or 8 goals (depending on the referenced document). A midfield maestro and a set piece expert, he compiled over a century of caps at international level while starring for Dire Dawa’s Cotton FC and Addis Ababa’s St. George at club level. And yet, there is no mention of his name anywhere on the EFF’s official website.

The end of the political standoff between the governments of Ethiopia and Eritrea spells a world of opportunities for the people of both states. Cross border trade and tourism have begun to thrive after the opening of the joint border for the first time since 1998. But also eager to capitalize on peace in the region are members of the sporting establishments of the respective countries. Talk of a friendly match celebrating the peace between the two states has gone on for months. Within weeks of the historical announcement, Ethiopian club side Fasil Kenema sent an invitation letter to the Eritrean National Football Federation (ENFF), requesting to commemorate the joyous occasion with a friendly match against an Eritrean club side. The ENFF responded positively, replying in an open letter that it would prepare for such an event. Eritrean sporting news outlet Eritrean Football have reported that a long awaited “peace match” between Ethiopia and Eritrea will likely be held sometime next year.

There has been no such eagerness expressed by the EFF. Unlike some Ethiopian club sides and members of the national team, who have reiterated their willingness to take part in a venture bringing the two peoples together, those heading the country’s game have been somewhat guarded in their responses. For years, the EFF has been slammed by fans who bemoan what they say is the organization’s being run by a seemingly docile group of men with no background in the game. The EFF has taken every precaution to stay politically aligned with the regime and its narrative, but fail to exert the same sort of energy into revamping the national game. Even now, as a new era is ushered in across the Horn of Africa,

the spontaneity and innovation seen across the Ethiopian and Eritrean sporting worlds is thus far absent at EFF HQ. The Ethiopian Athletics Federation invited Eritrean runners to participate at this year’s Great Ethiopian Run in Addis Ababa, while the Eritrean Cycling Federation welcomed Team Ethiopia to Asmara to take part in the African Cycling Cup it hosted weeks later.

The EFF could truly prove to be a national asset and contribute to the reconciliation process by righting the wrongs done to the Eritreans who bolstered its ranks. Inviting a number of the living Eritrean footballing stars who gave it their all for Ethiopia back to the country to be reacquainted with the masses who adored and idolized them would go some way to healing the scars caused by the societal marginalization they were undeservedly subjected to. A heroes’ welcome at the stadiums where they established their reigns as sporting kings would certainly be the least the country could do at this point in time. Allowing them to reclaim their place in Ethiopian sporting history with all the dignity and glory it is supposed to encompass would not only facilitate the general rapprochement initiative, it could serve to inspire the youths of today to aim higher and aspire to reach the heights the old lions of yesterday did. But if they remain simply names inscribed onto yellowing files of old match reports collecting dust at CAF headquarters in Cairo, their achievements and a significant part of the two countries’ collective heritage will remain confined to the dustbins of history. A colossal loss.

Ethiopia may no longer be an African football heavyweight, but the country still boasts a respectable treasure haul of international accolades in comparison to its fellow minnows of the game. An AFCON crown and four regional CECAFA cup triumphs still puts the country up and above the majority of the continent. The likes of Tunisia, Morocco and South Africa are leaps and bounds away from the Walyas in terms of producing talent today, but they remain tied with Ethiopia with a single AFCON triumph a piece. Ethiopia’s trophy wins were earned by clinical and composed young men who answered the nation’s call when it needed them the most. It’s high time the nation pays its respects to those men, no matter what their nationality.

My name is Zecharias Zelalem